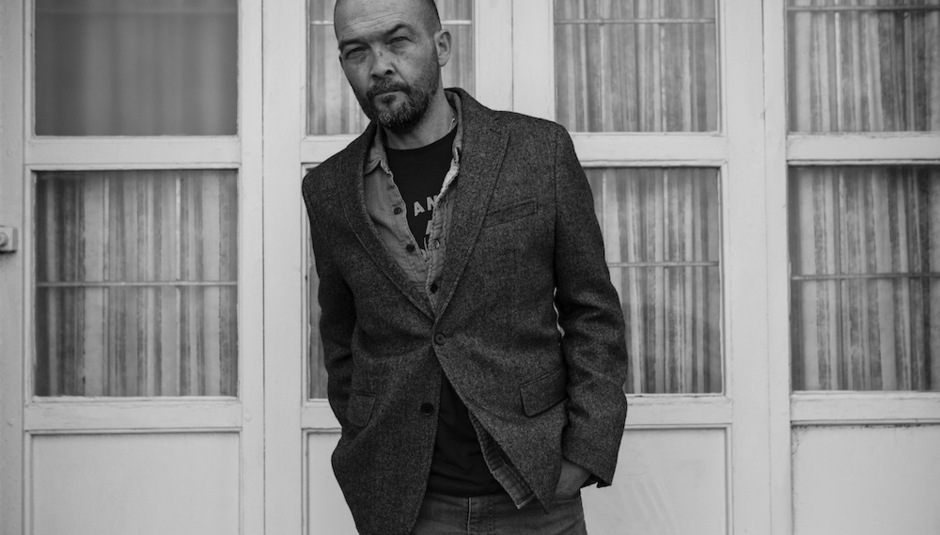

Hendra is Ben Watt’s second solo project of 2014 so far - the first being a memoir of his parents and his second book, Romany and Tom (listen below to an exclusive extract).

Recorded in London and Berlin, Hendra is a meeting of worlds: languid folk, distorted rock and fizzing electronics; in part a result of the album's two central collaborators, ex-Suede guitarist, Bernard Butler, and Berlin-based producer Ewan Pearson. The album also includes one other unexpected stellar cameo - Pink Floyd's David Gilmour, who adds plangent slide guitar and backing vocals on 'The Levels'. Here, Ben talks us through an exclusive track by track of the album and premieres an exclusive version of 'Forget', live with Bernard Butler at St. Pancras Church in London...

HENDRA

I was close to my half-sister, Jennie. She died unexpectedly in the autumn of 2012 aged only 58 from late-diagnosis lung cancer. She’d suffered from depression on and off all her life. At times it had been very debilitating. She finally got married aged 50 and ran a simple village stores in North Somerset with her husband. It was hard work. They had a little place they used to get away to, away from the intensity of living above the shop. She used to call it ‘Hendra’. I never knew what it meant. Was it mythological? Like the Hydra? I thought it was a beautiful word. After she died, I researched it. It is an old Cornish word meaning ‘home’ or ‘farmstead’. It was also the name of the road where her hideaway was located. After that it just slowly became the name of the album for all these reasons. The song is about her dreams of escape, and about resilience and hope. Musically it is a statement of intent. The interface of folk and rock and electronics. Which is where I tried to position the album.

FORGET

The lyrics were begun ten years ago as part of an abandoned project I started while running my label, Buzzin’ Fly. The project was called ‘Outspoken’. Three songs emerged from it - one with Estelle (‘Pop a Cap in Yo’ Ass’) and two with Baby Blak (‘Attack, Attack, Attack’ and ‘Old Soul’). They were attempts to merge spoken word with music for clubland. The lyrics to ‘Forget’ (originally called ‘Approaching Phantoms’ back then) lay around in a notebook until I realised the imagery in the verses - the Sussex Downs after rainfall, washing someone’s hair in a darkened house - would suit other songs I was writing for ‘Hendra’. I had recently bought a reconditioned 1976 Wurlitzer EP200a electric piano (with the help of some crowd sourcing on Twitter) and just sat down with the lyrics and the rest just tumbled out. The bit people remember - ‘You can push things to the back of your mind, but you can never forget’ - is part of the new stuff I wrote for it. Our past is made up of vivid moments, six-second ‘Vines’ of memory, some full of regret. Sometimes it hard to get past them, but in the end you have to evolve, to let those moments slide, tough it out.

'Forget', Live at St Pancras Church

SPRING

Midway through the writing of the album I was aware I needed a counterweight - something that began from a moment of light, not a moment of shadow. I cast my eye around the room looking for inspiration, and my eye fell on a book of sheet music on the floor at my feet for an album by the jazz pianist, Bill Evans. It was called - after the jazz standard - ‘You Must Believe in Spring’. Faith in small things, I thought. And that was the springboard for the track. I began right there and then. Simple major chords. Familiar. Rocking back and forth. I wanted to make the whole thing easily readable. It is about getting older, about finding solace in modest things. We kept the arrangement dry and unadorned, muting the drums with tea-towels to reduce their resonance. Out of this simplicity I wanted one big moment of magic and sparkle, like a flash of sunlight, and so we added a garland of backing vocals and Mellotron flutes to the bridge.

GOLDEN RATIO

Two guitarists who had the biggest influence on me growing up were the Brazilian Joao Gilberto and John Martyn. My dad was a jazz musician. I heard a lot of jazz growing up and was drawn to the warm sound of the Getz-Gilberto albums as a child, and when I started playing guitar I wanted to learn those warm Brazilian bossa nova chords. And then in my teens a boy from school played me John Martyn and I heard the approach updated. It was a light-bulb moment. I bought a delay pedal and leant how to slap the body of the guitar on the off-beat while playing rich voicings on the fretboard. I experimented with the sound on my early recordings for Cherry Red in 1982 when I was nineteen. It reappears on and off during my time with Tracey in Everything But The Girl for example on ‘Rollercoaster’, and ‘Golden Ratio’ is its latest incarnation. The main difference this time is the tuning of the guitar. It is an odd open-tuning in D minor that I stumbled upon. The lyric is about trying to shrug off self-doubt, about trying to live in the moment and is set on the beautiful cliffs and downland above Studland in Dorset.

MATTHEW ARNOLD’S FIELD

I wrote this song the year after my dad died in 2006. It tells the story of the journey I took to scatter his ashes. I wrote the song unexpectedly and it lay unused for several years. With no intention to record an album I abandoned the song and chose to re-tell the story - in prose form - in my new book about my parents’ marriage, ‘Romany and Tom’. Then, when the ‘Hendra’ got off the ground in early 2013, Tracey said I should record it anyway, and I thought it would be interesting to have two versions of the same story. In the end it became a millstone round my neck. It suddenly seemed like a very important song. In the end it took three attempts to record it and it was very nearly abandoned. Then on the very last day of the album, as we were mixing the final tracks at Air Studios in London, me and Ewan Pearson (the album’s producer) dashed back to my house and in a moment of enforced spontaneity, recorded the track in one take in my basement, and before we could over-think it, drove back to Air and mixed it.

THE GUN

This was another lyric that began life as part of the ‘Outspoken’ project (see ‘Forget’). It followed a trip I made to Southern California about ten years ago. I had found myself accidentally walking through an ocean-front gated community while out for a beach walk and was struck by its opulence yet intimidating emptiness. It coincided with two newspaper reports I had read - one about about escalating casual gun ownership and one about a stray-bullet killing of a young boy. The story just formed in my mind. Then last year I returned to the west coast on a road trip I made with an old friend of mine. The lyrics came back to me and I finished off the song. Much of album has a strong sense of location, a visual sense of geography that looms on the shoulders of the characters. I wanted to give ‘The Gun’ that atmosphere too. The lyric determined the musical mood - burnished guitars, rising waves, low amber sunsets, distant Hammond organ. I wanted a deep rich sound, where the low E on the guitar is tuned down to low C in an open voicing. At first I played the part on an acoustic guitar, but then I moved it onto my 1968 Gibson Byrdland, a hollow-body electric to give it more edge.

NATHANIEL

This is the other song that came out of the road trip I made down the west coast last year. We were driving through Oregon and passed through the small coastal town of Tillamook. And, as the song describes, there in an empty parking lot was a trailer emblazoned with the simple words - Nathaniel, We Will Always Love You. I immediately registered it as roadside memorial and it seemed so brutally and movingly simple. Later I researched it - and yes, it had indeed been put up after a local boy had been killed in a car wreck five years earlier. The plainness of the memorial seemed in direct contrast to modern obsession with ‘secondary grieving’ and the huge impersonal shrines of flowers and toys that are established after a moment of trauma or disaster these days, as complete strangers weigh in on the private grief of individuals. TV coverage amplifies it, which I often find mawkish and off-putting. Musically I tried to capture some of these feelings - a sense of anger, of careering out of control, of the stages of grief.

THE LEVELS

This is another song written in the aftermath of my half-sister’s death. I wrote it for her husband. It is a simple song. About dealing with loss. It is set on the low-lying Somerset Levels where they got married. The flooded fields, the long vistas across the flat land - they seemed to conjure up a lot of the feelings I was trying to capture. When we were recording I played the main guitar - a solid body Les Paul - really loud through a series of delays and reverbs with microphones placed wide around the room to get a sense of space. We then played the part back through more speakers and I lay on the floor in the studio manually adding more echo and delay in the cacophony of sound. The song also features Pink Floyd’s David Gilmour. His involvement was completely unplanned. We met for the first time just before the album sessions and got on well. We spent a day together at his studio near Brighton. Back in London, when recording ‘The Levels’ I though he would great on the track - that plangent sound. I just called him up and he added slide guitar and backing vocals and a bit of bass. Amazingly sensitive playing.

YOUNG MAN’S GAME

It’s a song about getting older in clubland, specifically being a DJ in clubland. The dancefloor never ages. It constantly renews. But the travel and the hours and the lifestyle on the DJ start to take their toll as the years go by. I started late as a DJ - I was in my thirties. The partying is the easy bit. It’s the recovery time that gets longer. I tried to write unsentimentally and honestly about it, to add a few wry jokes. I also thought it would be self-deprecating and ironic to couch it in a country-folk song.

THE HEART IS A MIRROR

We take our problems wherever we go. Introspection exists even when confronted with moments of great natural beauty. I started writing it while driving the coast road down through Washington state last year, past the forests and Columbia river delta, where whole hillsides were covered in flattened trees, not caused by felling and logging, but by a huge storm. It felt vivid and powerful. And I though how back home relationships can often get derailed by one partner’s continued self-absorption: the petty victories and the touchiness stem from issues over status and self-worth; misunderstandings happen. This song is about all that stuff. But it ends with an effort at self-recognition, at shrugging off the face in the mirror, at accepting love when it is handed to you. It is an upbeat end. That seemed important in the wake of all that has gone before on the album, because that, in the end, is what matters. In the studio I wanted to get close to the idea Stevie Wonder uses on Talking Book where a sinuous synth line snakes behind the vocal, part beautiful, part proud, like a second train of thought ghosting the lyric. Jim Watson plays the Moog on the album. Great playing.

Hendra is out now via Caroline.