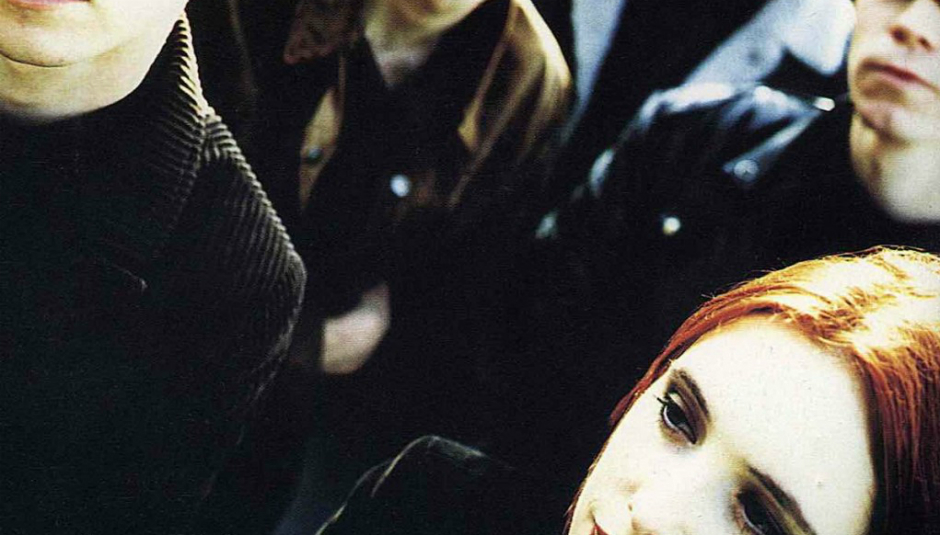

To say Slowdive and their second album, Souvlaki, weren’t appreciated in their time is an almost comedic understatement. Richie Edwards famously said he hated the band more than Hitler and there’s the oft-quoted Melody Maker review in which the critic said he would rather drown in porridge than listen to the album again. The band have recounted the story of a gig on that tour where they watched a woman mop the floor while they played. It’s a scale of derision that would be maudlin at best in the film version.

Hyperbole aside, the fact was that Souvlaki was released to a British press that had moved on to Britpop and couldn’t be bothered. In America, where being a contemporary fan of shoegaze and Britpop was totally compatible, their label SBK bungled the release, sending the band on promo tours without an album to sell. Unlike their Creation labelmates, Slowdive didn’t have a hit like Ride, and despite the difficulties of recording Souvlaki, they didn’t achieve the mythos of My Bloody Valentine. They might have been also-rans of the era, swept under the rug as band members went on to play alt-country or electronica, but time has a way of recontextualizing things.

Souvlaki is such a stellar specimen of shoegaze that it’s hard to imagine it wasn’t always lauded. It’s been 25 years since Slowdive released their masterpiece, and Souvlaki is nearly perfect not least because it’s the moment when Slowdive reached their full potential. It might have been because Alan McGee had them throw out the first few dozen songs they submitted, or because Neil Halstead and Rachel Goswell had a strained-enough relationship that their lyrics weren’t total nonsense, or because Brian Eno shared some of his mojo.

It could also be that after four years together, the band had finally formed their own identity. Where Just For A Day has a single, vaguely 90s timbre, Souvlaki is multifaceted. Neil and Rachel’s vocals are defined and individual and, when paired together, harmonize beautifully instead of squishing together into a lone flat voice. The initial drones and borrowed song structures gave way to the kind of shimmer that is equal turns pretty sparkle and migraine aura. ‘Sing’ has a weird haze around it that lets vocals, electronic tones, and the odd bass note come into focus and quickly bleach out again. ‘When the Sun Hits’ is made of light that peeks through the curtain on the verse and blinds you in the chorus. And it says a lot when an album features Brian Eno and the most remarkable production on it isn’t by Eno – the dizzying live mix and the endless delay on ‘Souvlaki Space Station’ makes it a miracle that the song’s kaleidoscopic textures can be faithfully recreated live.

It didn’t take long after Slowdive’s initial split in 1995 for the world to realize what it had missed out on. 4AD’s Ivo Watts-Russel was completely enamoured of Souvlaki closer ‘Dagger’, recording a cover with his post-Mortal Coil project the Hope Blister and signing the remaining Slowdive members as Mojave 3 after Creation dropped them. The anomalous acoustic song in their catalogue almost doesn’t register as acoustic at all; the way the guitar chords ricochet off themselves backed by pin-prick keyboards is neither the stuff of pop music or coffee shops.

By the early 2000s, their influence was being felt through the Morr Music tribute album and in the influences sections of MySpace music profiles (regardless of what those bands sounded like). It was around this time that a boy gave me a copy of Souvlaki — the American edition, released in 1994 with electronica-leaning bonus tracks — because he thought I would like it and he was right; I loved it immediately. On ‘Alison’, when Neil sings “I’m just floating” I felt like I was, too. I floated along the vibrato of the guitar, through the rises and falls of ‘Machine Gun’ that are like changes in atmospheric pressure, and felt myself spinning between the verses of ‘40 Days’. Absent of any reference points, I had never heard anything like it before, and I didn’t yet realize that my favourite guitar music would be songs that don’t sound like they have guitars on them at all. It was music that, if I played it loud enough, I was sure I’d hear something different, something I didn’t hear the first time or the 100th time.

I still hear something different in Souvlaki every time I listen to it. I hear subtleties in the production that I missed because I was dazed by the initial impact of music, and I hear whole songs differently because I filter differently now than I did as a teenager. We all have music that we pinpoint to a specific time and place — my relationship with Souvlaki is my determination to separate that album from a specific time and place. The complexity of the album is in a large part of the reason why I’ve worked to maintain my own complex relationship with it over the last 15 years.

The boy who gave me the record removed himself from my life shortly afterwards. I didn’t handle that well, but I wasn’t handling much well at the time. My serotonin had been on a leave of absence for a year already, but it would be at least another year before doctors figured that out. I was stumbling through a period of adjustment in a new city with a chemical imbalance and a beautiful record that was quickly becoming associated with all the ways I didn’t have it together.

For the next year and a half, I carried Souvlaki with me hoping it would soundtrack something other than my maladjustment. I took it with me to a new apartment; I took it with me for an extended stay in London (unfortunately timed for being down the road from Russell Square on 7/7/2005); I took it with me as I lost people I cared about because I left them or they left me or life left them. But I loved this album enough to try to forge a new relationship with it, one independent of awkwardness, broken hearts, absent serotonin, or bombs on buses.

At some point, I accepted that Souvlaki was an album that made me feel sad and made a point of listening to it when I felt sad. I listened to it when I felt that physical weight that comes with depression, the numb indifference so neatly summarized in ‘40 Days’: “If I saw something new / I guess I wouldn’t worry / If I saw something new / I guess I wouldn’t care”. I listened to the album when I wanted to cry because I thought crying might release something; when I didn’t cry I still imagined something had been filtered through it.

Giving yourself over to a feeling, even a negative one, is a useful way of moving yourself past specific reminders of people, places, or events. It’s convenient that Souvlaki is an album suited to feeling. It’s music you can surrender yourself to, that will completely overwhelm you if you let it, that will thread itself through your brain until thoughts fade and emotions take over. ‘Souvlaki Space Station’ closes in around you; ‘When the Sun Hits’ bursts from within you. The opening notes of ‘40 Days’ are a blow to the head; ‘Dagger’ is a chest compression.

Souvlaki came into being in the wake of a romantic split between Neil Halstead and Rachel Goswell, and there is an undercurrent of this tension that can’t be ignored. ‘Dagger’ is a break-up song if ever there was one, with an added layer of crippling depression. ‘Here She Comes’ has a hopeful longing. But Souvlaki is not a break-up album and 25 years later the prior relationship between the two singers and guitarists is not the defining narrative of the band; it’s merely a part of the story, the way the press’s dismissiveness is part of the story.

As I said, time does have a way of recontextualizing things. It’s the reason why you can listen to Souvlaki now and not think it’s specifically of the early 90s, the way certain grunge or Britpop or “alternative” albums are. It’s the reason why you can watch the band perform these songs now that they’re in their 40s and not feel it’s a nostalgia trip. Some music belongs to a specific time and place, and some music can be rescued from a specific time and place — by both the listener and the band.